Last year, I wrote about my 3rd great grandmother, Sarah H. Hill, and used her as an example of a “brick wall” ancestor. Her name has stared at me from family tree charts and my Ancestry.com tree for a long time, frustrating me to no end that I had no idea where she came from. As with any project, certain family lines were prioritized over others, and I just wasn’t able to devote much time to researching Sarah beyond searching through wills and census records on Ancestry.com. I had a feeling that either the records that could shed some light on her background were no longer extant, or her history might be buried in some obscure court documents that I could only access at the county level. I put Sarah away and did not return to looking for her origins until yesterday afternoon when I just had a good feeling about her. And to my great astonishment…

I FOUND HER FAMILY!

I was so amazed and beyond excited to be reading Chancery Court minutes that so succinctly named her siblings, father, and three grandparents. I can’t take full credit of making the “discovery” by myself or make it sound as though I traveled to Tennessee and sat in the Marshall County archives pouring over dusty minute books. This time, Google is the real hero, that and my ability to type in “Sarah H. Hill Alvin Johnson” into the search engine.

I did just that, and would you believe it, the first hit was their names found in a book entitled Tennessee Tidbits 1778-1914 vol. 4 by Marjorie Hood Fischer. Part of the book had been scanned, but not its entirety. From what I could tell, the author took abstracts of interesting court minute entries from across the state and compiled them into several volumes. Really, it was just luck that Sarah was in the volume at all. What was even more astonishing is she isn’t found in the book once, but several times!

Sarah, her four siblings, her siblings’ husbands, and their trustee were complainants in a suit filed against their father’s estate in the 1840s. At first glance, I suspected that this Sarah was my Sarah, but what clinched it was the fact that her first husband, Alvin Johnson, is named in one of the suits.

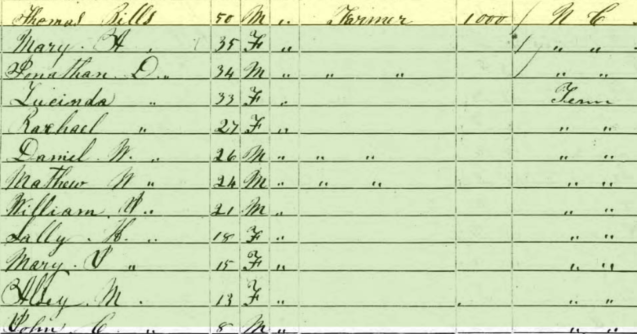

Here are the familial relationships noted in the court minutes (these minutes spanned several years in the 1840s):

Elisha Bagley – Grandfather

Richard Bagley – Grandfather and father of Robert W. Hill

Lydia Hill – Grandmother (her name is mentioned although in the minutes her relationship to the 5 siblings is not specified)

Robert W. Hill – son of Richard Hill and father of 5 children

1. Mary Ann Eliza Hill m. William Webster

2. Amanda Jane Hill m. James Turner

3. Sarah Harriet Hill m. Alvin Johnson

4. Martha W. Hill m. Abner J. Cole

5. William Jasper Hill

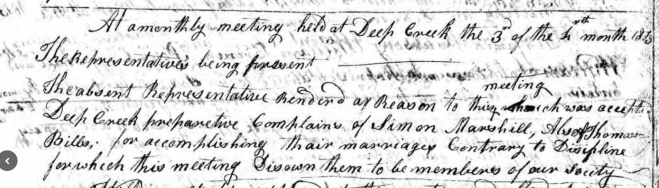

Court Case – James C. Record et al. vs. Robert W. Hill

James C. Record as the Trustee for Mary Ann Webster wife of William Webster, Amanda Jane Turner wife of James Turner, Sarah Harriet Hill, Martha W. Hill, and William Jasper Hill, sued Robert W. Hill, the complainants’ father. The abstract doesn’t specify what the case is truly about. It is mentioned that their maternal grandfather, Elisha Bagley, put in trust to James C. Record for the 5 children four enslaved people – Milly and her children Patrick, Roseannah, and David Crockett – on 25 May 1835. The minutes also mention another enslaved person, Simon, who was left presumably to either Robert W. Hill or his 5 children in the will of Richard Hill.

It seems that this case concerns the 5 heirs of Robert W. Hill, Richard Hill, and Elisha Bagley receiving their inheritance. The interesting part is that their father, Robert, was alive at the time; they weren’t suing his estate.

No date is given for this suit, but based on the daughter’s marriages, it took place between 26 January 1840 and 20 November 1843.

Court Case – Lydia Hill vs. James C. Record, James Turner, et al.

A second court case – Lydia Hill vs. James C. Record, et al. – dated 13 March 1844 gave a little more insight into the family relationships. The abstract only records that it concerned the minority of Sarah Harriet and William Jasper and that no guardian had been appointed to them. As their father, Robert, was still alive, this was a guardian ad litem, an impartial person assigned to protect their interests during their inheritance dispute with their father and apparently Lydia Hill, who I could see was another relative (I didn’t know at the time that she was Robert’s mother). The court chose George Elliott to fill this role.

On 10 June 1845, the guardianship issue was again addressed in court. By this date, Sarah had married her first husband, Alvin Johnson, and so only her brother was still considered a minor. It was decided that the portions inherited by Sarah and Martha were to be settled on them without the control of their husbands, Alvin Johnson and Abner J. Cole, respectively.

On 10 March 1847, a petition was submitted by John R. Hill, stating that Robert W. Hill had five children, and they were the only people entitled to the land given to them in Richard Hill’s will.

Soon after, Mary Ann Webster, Sarah’s oldest sister, also submitted a petition to the court asking that her interest in her grandfather’s land be vested in the land of Sarah Haywood (probably another relative).

The abstracts leave a lot to be desired in terms of what exactly the cases were about and family dynamics. Not that I am complaining; I am VERY grateful for what I do have. It just leaves me anxious to know more!!

But Wait, There’s More!

Sarah appears again in Tennessee Tidbits! And what I read in the second entry explains one of the biggest questions I had about Sarah: if she was the same person who married Alvin Johnson and Nathan Calloway Davis, why was her name listed as Sarah H. Hill in both marriage records? I assumed she would be Sarah Johnson when she married Nathan. The reason: DIVORCE!

Of course divorce! That makes sense.

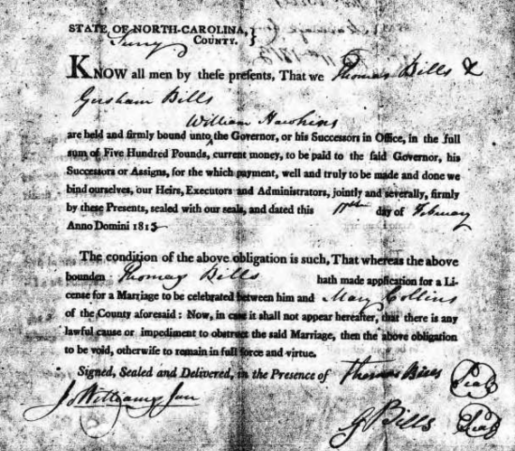

Sarah H. Johnson filed a bill for divorce on 22 August 1856 against her husband, Alvin A. Johnson. She stated that they were married in Marshall County, Tennessee (on 17 September 1844 when she was 17 years old). They separated four years prior to filing, so about 1852. She charged him with adultery with “sundry lewd women,” including someone whose last name was Delany. The court granted her divorce and restored her maiden name, Sarah H. Hill. This is why her named was “Sarah H. Hill” on the second marriage record to Nathan Davis.

Sarah also asked that the money held (probably in trust for her) by James B. Tally – the money given to her by her grandfather Elisha Bagley – be given to her.

I want to believe that she did receive her money and that she was finally free of a man who probably made her life very unhappy. The coward didn’t even bother to show up to court for the proceedings.

When she married Nathan Davis on 23 September 1858, she was a divorced woman using her maiden name once again.

Inheritance Issues

Of course once I found this information, I kept digging to see what else I could find. I was desperate to find more about Sarah’s siblings, parents, and grandparents. The court cases indicated that the wills of Richard Hill and Elisha Bagley existed in the 1840s, so I had some hope that I could find them now. Unfortunately, in that area of Tennessee, there were several courthouse fires that destroyed records. I was pleasantly surprised that both wills I was searching for do exists and were on Ancestry.com.

I won’t go into too much detail here (I may want to use these for future posts), but I do want to relate the bequests in them that are relevant to Robert W. Hill and his 5 children.

Will of Richard Hill

Richard Hill, father of Robert W. Hill and grandfather of Sarah Harriet Hill, wrote two wills, one on 7 February 1832 and the second on 30 May 1832. The later will was the one most likely used for the estate settlement, although I have not seen that either was recorded as probated. Both wills were entered in the Maury County will books.

It begins, In the name of God Amen I Richard Hill of Maury county and state of Tennessee being in a low state of health but of sound mind and memory do make and ordain this my last will and Testament…

And then proceeds with specific bequests. The ones of interest right now concern Richard Hill’s wife, Lydia, and Robert W. Hill and his children:

I give and bequeath to my wife Lydda two negroes named Sarah and Lizza I also lend to my wife Lydda the following that is Joanna Chainy Will Thomas Willis Aaron Isaac and Jacob for her own use and benefit during her natural life…

I also lend to my said wife Lydda all that part of my plantation in Maury County which lies south of Thomas Branch during her natural life…

I also lend to my said wife all my household and kitchen furniture beds bedsteads and bed furniture and all my plantation and farmin utensils in the same manner…

I give and bequeath to the children of my son Robert jointly one negroe man named Simon, and all my land that lies north of Thomas’ branch, and also at my said wifes death or marriage, all my land lying south of Thomas Branch, to them and their heirs forever.

Item my will is that all the personal property or estate that I have lent to my wife as above mentioned, be at her death be divided in the following manner, that is to say My son Roberts children one third…

These bequests show the players in the 1844 case of Lydia Hill vs. James C. Record et al. a little more clearly. Lydia was Richard’s wife and (verified in yet another court case) Robert W.’s mother. Lydia Hill was taking her grandchildren – including Sarah H. Hill – to court in the mid 1840s over some discrepancy over their inheritance of the slave, Simon. The later court cases over the land must have taken place after Lydia’s death as her grandchildren weren’t set to inherit any of that real property until then.

This will made me wonder why Robert was skipped over in favor of his five children. Perhaps Richard had already given his son property. Or, perhaps Richard and Robert were not on the best of terms by his death. I think the former is more likely. Another court case – Levi Cochran vs. Robert W. Hill – makes it clear that Robert was living with his parents at the time of his father’s death and even after to help his mother manage her business. But, I will need to look at the court minutes in full to have a better understanding of the circumstances.

It seems that by 1847 the five Hill heirs had probably received their interest in their grandfather’s land, which means their grandmother died around that time.

Elisha Bagley and a Deed of Trust

Elisha Bagley died on 21 May 1858 while living in Lincoln County, Tennessee at the age of 82. His first wife, Sarah Wilkins, died in 1830. He remarried 9 years later to a woman named Elizabeth Todd.

Elisha and Sarah’s daughter Elizabeth married Robert W. Hill around 1820, and their first daughter was born in 1824. Sadly, Elizabeth died on 19 May 1835 at the young age of 33, leaving behind five children. According to the Marshall County minute books, Elisha Bagley put into trust for his 5 Hill grandchildren the four enslave people – Milly, Patrick, Roseannah, and David Crockett – on 25 May 1835, just six days after his daughter’s death. He probably intended them to be Elizabeth’s share of his estate. Again, this is just a guess as I haven’t read the actual deed yet.

However, that doesn’t explain why the 5 Hill grandchildren would take their father, Robert W. Hill, to court, as he was not the trustee of Milly and her children. That was undertaken by James C. Record. This just shows that there is more to the story.

But what funds held by a James B. Talley was Sarah referring to in her divorce? I am just guessing here, but I believe the enslaved people must have been sold, and Sarah wanted her share of the profit given to her. The funds could not refer to anything in Elisha’s will as although he wrote it on 29 November 1855, he didn’t die until 1858 and Sarah’s divorce took place in 1856. James B. Talley was Sarah’s uncle, the husband of her mother’s sister, Bethenia Anne (Bagley) Talley. Why he had Sarah’s money, I have no idea. Again, more questions have come up that can’t be answered until I see all the records in full, not just abstracts.

Will of Elisha Bagley

When Sarah’s grandfather, Elisha Bagley, wrote his will in 1855, she was separated from Alvin Johnson but had not yet filed for divorce. She wouldn’t marry Nathan C. Davis until a few months after his death in 1858. So what did Elisha leave to Sarah and her siblings in his will?

Item Sixth – I will and bequeath to the heirs of the body of my deceased daughter Elizabeth C. Hill one fifth of my real & personal property.

However, some problem seems to have arisen during the settlement. The will was proved in court in 1859, but in 1871, the property is still being settled! James B. Talley was at some point appointed the administrator. Whatever dispute happened, a judgment was rendered in the Circuit Court in 1871. This seems to be the James B. Talley vs. W. F. Kirchival case. However, another case – Mary Webster et al. vs. James B. Talley – was filed in the Chancery Court in Lincoln County around the same time .

Mary Webster is, of course, Mary Ann (Hill) Webster, the oldest sister of Sarah Harriet Hill who was one of the prime movers in the cases brought against their father Robert W. Hill.

After judgments had been rendered, Mary Ann Webster, James and Amanda (Hill) Turner, and Nathan C. and Sarah (Hill) Davis finally received their portions of their grandfather’s estate.

Conclusion

In short, those abstracted court minutes in Tennessee Tidbits opened up several new branches of my family! I now have so many more questions about Sarah and her relations, and I am so excited to get my hands on the actual court minutes, deeds, and court cases.

Looking at these records reiterated to me just how difficult and sad life can really be. Sarah’s mother died when she was just eight years old, her father seems like he was a difficult man to live with, she married at a young age to a man who cheated on her, and her second husband died twenty years after they married. I hope that she found some happiness with Nathan C. Davis and with her own children.

She lived to be about 81 years and was buried next to her second

husband and some of her children on the Davis farm in Marshall County, Tennessee. I have no photos of her, but after these discoveries, I feel like I know her quite a bit better.